In a new series of large-scale ceramic works, Melsheimer draws inspiration from the plant Welwitschia mirabilis, which grows in the Namib desert of Namibia and Angola. Named after the first European to describe the plant in 1859, Welwitschia is inscribed within a legacy of 18th and 19th century European expeditions in which plant specimens were collected, taxonomized and added to botanical collections. In the case of Welwitschia, a double claiming thus occurred–of the plant itself and the right to name it.

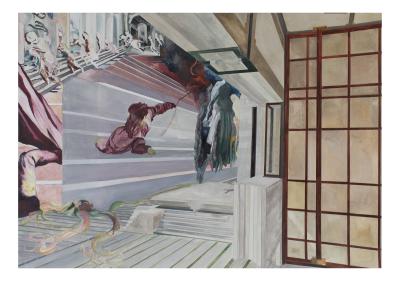

Melsheimer’s pieces depict Welwitschia-like forms that gradually merge with architectural elements. With their tentacular leaves interweaving and gradually engulfing the built forms, the plants appear to merge with the architecture, perhaps enacting their own organizational principles and right to claim.

The combined sculptural gesture of Melsheimer’s pieces, which gain in height as horizontal leaves intertwine with vertical walls, evokes another series of works with their own legacy of extraction and contested ownership: the Parthenon Marbles, now in the collection of the British Museum. Through this formal gesture Melsheimer makes oblique reference to the historic act of colonial acquisition and entitlement, as well as ongoing disputes over restitution.

For the artist, this historical act of appropriation finds an echo in postmodernism, where stylistic or theoretical citations from the past are decontextualized and juxtaposed in new form; a renewal of appropriation as plunder.

Melsheimer’s Metabolit sculptures (2019-20) are glazed ceramic forms that also combine organic and architectural elements. Leaf-like shoots are barely contained by their boxy surroundings. Bulbous concretions erupt from planar facades and cubic volumes, their mottled surfaces glistening and foaming as if still in motion. The result is a series of works in mutation: uncontainable, undisciplined forms exceeding imposed constraints.

Other works in the exhibition tackle hubristic architectural and technological projects through the 20th and 21st centuries, positing that the grand narratives of modernism persist, and that ideologies and styles are rejected only to be revived anew.

While some works seem to condemn our collective actions, especially in terms of our destructive relationship to the planet, other pieces display a more playful attitude. Small-scale ceramics and a series of stepped concrete forms bring the epic gestures and overarching narratives of modernism down to earth. Utopian architectural masterplans are reduced to ornamental planters and decorative household objects.

The ensemble of works in the exhibition suggests a reckoning with the legacies of modernism, as well as a recalibration of human relationships with the environment. Plants and other non-human species are shown to have their own potential for agency. Some works may be read as incursions of natural elements into manmade forms, or even menacing reactions to humans’ destructive ways. Conversely, these evolving states of engagement between organic and inorganic, between plant and manmade, are perhaps proposals for alternative forms of interaction: not antagonistic but rather hybrid or symbiotic. Melsheimer’s works suggest a type of multispecies kinship as defined by feminist theorist Donna Haraway: a making-with other entities, rather than self-making, in order to build more liveable futures together.

Text: Alexandra McIntosh